In these hours stadium choruses are rising on social networks for and against the self-styled agreement with Elon Musk’s Space X company, wanted by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

The principle

The fact stems from an indiscretion by Bloomberg, according to which this agreement is at an ‘advanced’ stage and around which the sum of $1.5 billion for the provision of telecommunications security services would revolve. First of all, we need to understand where the problem stems from, and to do so we can refer to a famous comparison between Mario Monti and the Prime Minister himself.

Monti’s words on the relationship with Musk were very explicit:

I believe that the personality whom the citizens have practically elected to govern the state must first of all respect the public power they manage. Never giving the somewhat provincialistic impression that we derive much satisfaction from the acclaim of the powerful, even when they are outside systems that we understand as orderly and would like to share. The privatisation of power was emphasised yesterday by the President of the Republic in very measured words, but indeed if one gives the impression of erecting a private gentleman great genius like Elon Musk to a form of moral protectorate of our country, well, in my opinion there is a loss of dignity of the state

The problem is therefore that Elon Musk, a private entrepreneur of undoubted talent and great power, can interfere with the governmental affairs of a state (in this case Italy) through his influence. There is also the problem of Musk’s ‘election’ as ‘defender’ of the state, which, by the way, is contrary to logical and political sense: it should not be a private individual who protects a state, but it should be a state that protects the private individual.

However, this questioned agreement seems not to have been sealed and, to give news of this, it is directly the Presidency of the Council with an official communiqué that states:

The Presidency of the Council of Ministers denies that any contracts or agreements have been signed between the Italian government and the SpaceX company regarding the use of the Starlink satellite communications system. The talks with SpaceX are part of the normal consultations that state institutions have with companies, in this case with those providing secure connections for encrypted data communication needs. The Prime Minister’s Office denies even more categorically the news, considering it simply ridiculous, that the SpaceX issue was discussed during the meeting with US President-elect Donald Trump.

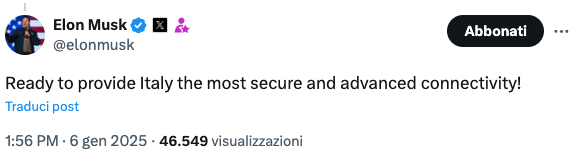

The release is marked 6 January 2025, but on the same day, after the release was published, at around 1.50pm, a Tweet from Elon Musk appears saying something apparently different.

Criticism

The criticism of the Italian government’s actions should, however, be put in a broader perspective: why would we need an Elon Musk? This question, in the writer’s opinion, is the real question. As of today, the European Union has 27 member states, and it is easy to imagine that in each of these states there are high-level companies capable of pooling their forces and guaranteeing a strong and secure technological development of the Union, yet this has not been happening for years. Perhaps the best answer was given by Mario Draghi during a high-level conference on the European pillar of social rights in La Hulpe (Belgium). On that occasion Draghi stated:

The fact is that Europe has had the wrong focus. We have turned inward, seeing our competitors among ourselves, even in areas like defence and energy where we have deep common interests.

On 9 September 2024, Draghi himself presented ‘The Report on the Future of European Competitiveness’: here is a very well done summary for those who want to know more. In essence, Draghi identifies 3 main areas for action:

- correct the slowdown in productivity growth by closing the innovation gap with the US and China.

- reduce high energy prices (EU companies still face electricity prices that are 2-3 times those of the US, while natural gas prices paid are 4-5 times higher).

- react in the face of a less stable geopolitical environment, increasing security, also in view of the fact that they can no longer rely on the United States as before.

In all three of these macro-activities, a detachment from dependence on the United States of America can be seen and, consequently, a repositioning of Europe at the centre of the scenario.

But if Europe is not at the centre, where is it?

The question is legitimate and important: if Europe is not at the centre of itself, where is it? More importantly, what is it doing? In recent years, individual countries have worked to create profit and expand the market; in a word, to generate development. But these activities have not really been coordinated and joined-up. For example, in the above-mentioned document:

The report shows that Europe did not capitalise on the first Internet-driven digital revolution and is now also lagging behind in revolutionary digital technologies.

A delay that, of course, leaves room for others including Elon Musk who was and is an entrepreneur (and now also a political representative).In marketing, the concept of positioning is strategic in order to be able to sell one’s product: Philip Kotler, one of the greatest exponents of modern marketing, has written entire books on this concept. Musk shows that he knows very well what positioning is: using all his resources and the lack of those of no less than 27 governments in Europe!

The relationship with government and politics

Regardless of political sympathy or antipathy, it is good to remember that the situation we have arrived at is not the result of the actions of a single government but of the (rather erroneous, slow and ill-advised) decisions of a series of governments that have followed one another over time. One has to be careful of Draghi’s words when he says‘Europe has not capitalised on the first Internet-driven digital revolution‘. The first Internet-driven digital revolution spans a period of about twenty years if not more. In essence, Europe has preferred to focus on something else: it has over time developed dependencies for defence, for energy, for technology, ignoring the importance these could have represented in the future. To criticise today‘s actions, for the sake of consistency, is to be equally critical of yesterday‘s actions.

One, a hundred, a thousand Musks

Elon Musk is not the problem, Elon Musk is. Musk provided Ukraine with the complex and crucial satellite communication system he owns: Starlink. This has played a key role in the current war conflict between Ukraine and Russia. Yet, being privately owned, this system could be ‘switched off’ at any time, depending on Musk’s own decision.

In 2020-2021, Facebook (today Meta) proposed to wire entire nations by bringing the internet to where it did not yet adequately reach. The problem in this regard is a serious one: many nations renounced this ‘contribution’ for fear that the connection would not be adequately free and that content would be filtered, producing an unwanted propaganda effect. In a 2021 Corriere della Sera article on this subject, it was written:

Among the projects presented by Facebook is the transatlantic submarine cable with 24 pairs of fibres that will connect Europe to the United States (with 200 times more capacity than the transatlantic cables of the 2000s).

The question, therefore, is not what Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg or other entrepreneurs want to do, but what Europe wants to do to bridge this gap that is now considered critical, even in the face of a geopolitical order now unbalanced in favour of war.

The ‘famous’ slow agony…

Making companies like Leonardo compete for Italy, Thales for France, Indra for Spain, is different from making them work together. Europe has the capacity to develop solutions and services internally to prove its autonomy and to create a more balanced and secure market with respect to major deviations. The recipe proposed by Mario Draghi is dramatically difficult and demanding, and the economist himself ‘jokes’ with a journalist when she asks him whether he believes the situation is to‘implement the relationship or die‘ and Draghi replies‘die no, but it will be a slow agony‘. Italy is in Europe and will experience contraction more than other countries, because it is less digitised and less competitive. Draghi explained that the slow agony will be a combination of the gradual reduction of available economic resources, together with an increasing ageing that we have already been hearing about for about a decade (the so-called demographic winter).

One must also consider the different way of approaching development: an entrepreneur is a professional who pursues business opportunities and, very often, even creates them unscrupulously. The important thing to understand is that the professional is the architect of his own destiny both in terms of profit and fame. His competence, his managerial skills, his unscrupulousness, are the weapons with which he conquers the market position and expands.

A politician is not. A politician is someone who is paid by the citizens to represent interests within the law. If a politician does not have characteristics such as competence, deontology towards his activity, he will not be able to be proactive towards the scenario he is supposed to govern: at most he will be reactive, but even then he will probably be so in a ‘reduced’ form. He will not be able to ‘see beyond the horizon’ and this is one of the biggest problems of those who are called upon to manage a technological transition.

With respect to the first case, Prof. Romano Prodi, in a recent episode of the TV programme Piazza Pulita, explains his view of the relationship between Musk and Trump:

There is this huge intersection between political power and economic power and they both […] have both political power and economic power with which they basically dominate every aspect of political economic life.

Over the years, Europe has been called an old continent, and not only because of its history but also because of its sluggishness. Much of this sluggishness is due to the protection of fundamental rights that other countries do not fret about, but much more depends on inaction and lack of development. Certainly the case of war is the most striking one: NATO’s role has diminished so much over time that it has become almost insignificant on the international scene.

In March 2024 an article in Linkiesta should have caused a stir in public opinion, the title is eloquent ‘Putin is no longer afraid to provoke NATO’. Inside it reads:

A few days ago a missile fell a few metres from where Zelensky and Greek Prime Minister Mitsotakis were standing. It could have killed them. Now we would be in a conflict, a global crisis. The second is the attack on Leonid Volkov, Navalny’s assistant. It took place in Lithuania, a NATO member. In these episodes I see Russia’s willingness to take greater risks because it perceives a weaker and more uncertain NATO. And such actions are bound to increase, unlike in the recent past when certain operations against the Western Alliance were limited.

In conclusion

There has been a change taking place for more than twenty years: a change that in the past was first ignored, then misunderstood and dismissed, and now appears in all its frightening complexity. The change is the inexorable technological-energy transition of which we are both actors and victims: it is a problem so complex and articulated that it would take time to be properly managed: time that we have largely wasted.

Today, with less time, fewer resources, and more geopolitical risks, we are called upon to do this in an emergency, and there are only two ways forward: the first is to rely on private entities such as Elon Musk, hoping for ethically unimpeachable conduct on their part in guaranteeing strategic services essential to the life of a state. The second is to rediscover the sense of union that was the basis of the European Union, which, after all, is also present in its name.