On 17 October, Italy will transpose the NIS 2 Directive(CELEX EU 2022/2555), and the expectation surrounding this directive raises a doubt: will the directive have any real usefulness or have we entered (for some time now) into a spiral of compulsive standardisation?

The issue around NIS 2

Europe needs to secure the technological infrastructures that guarantee millions of IT transactions on a daily basis and that suffer from many problems, including being mostly composed of systems created and distributed by non-European countries. This clearly becomes a problem when wars start breaking out and geopolitical instability begins to spread. Right now, Europe is witnessing the conflict between Russia and Ukraine that broke out in 2022 and the conflict involving the Middle East (Israel, Lebanon, Iran,…). In short, Europe is in a very particular geopolitical situation and it is in this situation that NIS 2 will be implemented by Italy on 17 October. Many wonder whether there was really a need for NIS 2: the first NIS directive was from 2016 and was repealed precisely to make way for its evolution because, the text reads,it ‘revealed inherent shortcomings that prevented it from effectively addressing current and emerging cyber security challenges‘. It is therefore expected that NIS 2 will project Europe into a modern, new cybersecurity framework, adapted to the geopolitical scenario and establishing strict criteria to be observed and enforced on a regular basis but it is known that expectations are often betrayed.

Utility or compulsive standardisation?

Within NIS 2 there is one article that, more than the others, has attracted the attention of readers: it is Article 21, which contains the main protection measures to be referred to by those affected by the Directive. It is precisely Article 21, however, that represents the first paradox of the Directive; for those accustomed to considering cybersecurity a normal requirement to be referred to, NIS 2 does not introduce any really interesting novelty but re-proposes decades-old concepts and arguments that are simply not observed. Let us give a few examples to make ourselves understood.

Article 21 (d) speaks of‘supply chain security, including security aspects concerning the relationship between each entity and its direct suppliers or service providers‘, what is commonly referred to as the supplier network or by the foreign name supply chain. NIS 2 establishes an obligation to check the security credentials of suppliers, an action that is already routinely done by companies accustomed to taking the context of IT (and not only IT) security seriously. The checking of suppliers is necessary to avoid problems and interruptions in the provision of services, with consequent repercussions on the financial and reputational aspects of the company. This control is performed by checking financial soundness, partnerships, public balance sheets, searching the dark web for information that may involve the supplier. These are normal activities in business management and many companies are already in the habit of checking the reputation and credibility of their suppliers.

Article 21 point (j) speaks of the‘use of multi-factor authentication solutions or continuous authentication‘ mechanisms that should already be routinely used by those who have a normal view of IT security: recent measures of the Data Protection Authority have, in fact, noted the presence or absence of such a security measure. The measure that concerned ASL Napoli 3 Sud (No. 9941232), for example, states the following:‘as of the date of the final notification of the privacy incident, the entity has effectively adopted multi-factor authentication for VPN connections‘. Multi-factor authentication has been present for years on all major operating standards in the world and is simply ignored for reasons of indolence and negligence.

Article 21 (g) talks about‘basic cyberhygiene practices and cyber security training‘, which are widely introduced and used in many companies that, for example, offer technical IT support or handle customer data and devices and therefore need to be more careful. In many companies, internal staff are trained on the latest threats through courses, newsletters, etc.. However, it is well known that just as often, training becomes just one item to be crossed off the list of things to do in order to be compliant; an example? The GDPR in Article 29‘The controller, or any person acting under his authority or under the authority of the controller, who has access to personal data may not process such data unless instructed to do so by the controller, except where Union or Member State law so requires‘. but often you find staff who are not really qualified despite the many training courses they have undergone.

One could go on with the other aspects of the Directive and some of them will also be reported below, but if one wanted to make a criticism of the text of the Directive, one could say that there is no real innovation with regard to these measures and this raises the question as to how innovative NIS 2 really is and how much we need it. Because, if on the one hand it is true that we continue to have cases of data breaches also coming from the chain of suppliers (like the case of June 2024 with the ASST Rhodense), it is equally true that it will not be the umpteenth Directive that will solve the problem. We have general regulations, specific regulations, European regulations, national regulations, but we probably do not have the right number of controls and sanctions. Consider what happened in May 2022, when ACN presented the Italian Cybersecurity Strategy. On that occasion:

Someone among the journalists asked whether sanctions are ready for those who do not comply with the new strategy, and this was confirmed by both Gabrielli and Baldoni, specifying that these sanctions will be even ‘heavier’ than the previous ones. However, it has been made clear that the attitude will not be punitive and intimidating, but supportive and accompanying to a transformation of IT security for those entities that are not ready. Objectively, this is an attitude that can only be partially shared: since 31/12/2017 (the date when AgID’s Circular 2/2017 came into force) very few public entities have taken steps to adopt them. More than four years have passed, a sufficient period to be understanding and ‘accompany’ the slowest P.A. in the change. It must be considered, among other things, that the most virtuous ones have not seen any benefit from their timely reaction but have seen how the less virtuous ones have been ignored in their static nature.

We continue to regulate without carrying out adequate checks to recover situations of blatant negligence as happened in the last data breaches in which some public structures continue to manage access credentials to systems and services on ‘txt’ files. We continue to regulate by introducing constraints, measures, and obligations, but the feeling is that there are not the necessary checks to enforce these constraints, and sometimes the doubt arises that it may be regulatory compulsion.

Is it regulatory compulsion?

It is a regulatory compulsion because for more than ten years, IT has been espousing standards that provide for computer hygiene rules, that provide for the use of cryptography, that provide for high security standards such as multi-factor authentication, that provide for backup policies, disaster recovery and operational continuity. Standards that provide for access control management, vendor auditing, personal data protection through risk analysis, impact assessments, vulnerability assessments and penetration tests, but then, if standards already exist that provide for all this, what need was there to produce an NIS 2 as well? Wouldn’t it have sufficed to enforce what already exists? And again, if one is already unable to conduct sufficient checks for compliance with the existing legislation, how will one check the newly added one?

Some examples

By legal obligation, public administrations must espouse Circular 2/2017 containing the ‘Minimum ICT Security Measures for Public Administration’. These measures are a reworking of the Critical Security Controls in version 6 (they have been analysed extensively on this site) and that version is stuck in 2016. In August 2024, version 8.1 was introduced: would it not have been more appropriate to update the Minimum Security Measures from version 6 to the new version 8.1? Perhaps someone may think that these standards lack the freshness of NIS 2, that they are lacking in something, and then it is useful to give some examples.

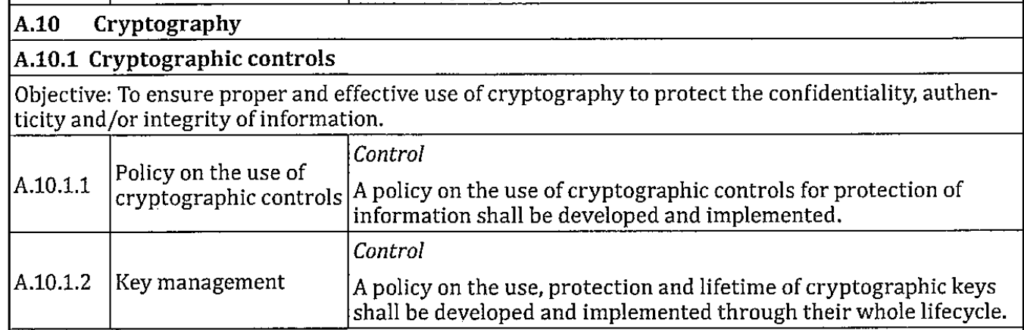

Let us take as a first example the use of encryption, a much-discussed topic in NIS 2 but already widely expected as an obligation since 2016 for P.A. Rule 10.3.1 of Circular 2/2017 states the need to“Ensure the confidentiality of the information contained in the backup copies by adequate physical protection of the media or by encryption. Encryption carried out prior to transmission allows the backup to be remote even in the cloud‘. If we consider Circular 2/2017 too narrow an example, we can rely on one of the world’s most important standards. ISO 27001, for more than a decade includes rule 8.24:“Standards for the effective use of cryptography, including cryptographic key management, shall be defined and implemented.” For example, in ISO 27001 of 2013 (second edition) the controls were equally present.

Let’s take multi-factor authentication as a second example, we know that NIS 2 requires the use of such technology but even this adoption is not new: just think of rule 5.6.1 of Circular 2/2017 which requires“Use multi-factor authentication systems for all administrative access, including domain administration access. Multi-factor authentication may use different technologies, such as smart cards, digital certificates, one time passwords (OTP), tokens, biometrics and other similar systems.” In this sense, ISO 27001 makes a more generic but nonetheless important contribution; rule 8.05 concerning secure authentication states that‘Secure authentication technologies and procedures shall be implemented on the basis of information access restrictions and the specific thematic access control policy‘. This rule was also provided for in the 2013 version of the same standard (control A.9.4.2) albeit in a more generic but equally significant form.

Not to mention that in the banking sector, for example, access to an electronic payment requires two-factor authentication as of 31 December 2020, as stipulated by the Payment Systems Directive (PSD2, EU Directive 2015/2366) through multiple verifications:

- “Something you know’, something only the customer knows (password, PIN, etc.)

- ‘Something you have’, something only the customer has (smartphone, bank token, etc.)

- ‘Something you are’, something that uniquely identifies the customer (facial recognition, fingerprint, etc.).

Take a third example: the use of cryptography: NIS 2 states the importance of adopting“policies and procedures relating to the use of cryptography and, where appropriate, encryption“, is this new? Again, one could cite Circular 2/2017, which for over five years has provided Rule 8.24:“Standards for the effective use of cryptography, including cryptographic key management, shall be defined and implemented.”

Take a fourth example regarding supply chain security. NIS 2 was considered by many to be groundbreaking for addressing this issue, ignoring the fact that ISO 27001 has for years included control 5.19:“Processes and procedures shall be defined and implemented to manage the information security risks associated with the use of the supplier’s products or services.”

Does it make sense to regulate in this way?

Is this the freshness, the novelty that is needed and offered to us by NIS 2? It is worth asking ourselves this question, especially when we have a regulatory framework on which various types of regulations already insist, for example the text of the GDPR for the personal data processing part, Circular 2/2017 for public administration. In short, NIS 2, which is a European directive, in many ways overlaps with what is already in place, and it is therefore reasonable to assume that there is a surplus of regulations with numerous overlaps.

It is good to repeat a concept: the problem is not just the ‘regulatory production’ but the lack of compliance. Those involved in cybersecurity are well aware of the poor measures that have followed the GDPR and the state of many public and private technological infrastructures, which are far from being compliant with any of the aforementioned standards. The ‘bogeyman’ of penalties, which fuelled intentions to come into compliance back in 2016, is now a memory that hardly anyone believes in anymore. Eight years have passed and we have data centres losing data without any control, difficulties in restoring, inability to administer data, we often read public communications from entities claiming not to know what data was lost as a result of a data breach. None of this is solved by adding one regulation, yet another, to the landscape of existing ones.

Conclusions

NIS 2 is an important text but does not add much to the existing scenario, especially for those who have invested in IT security seriously and competently over the years. Companies that have taken standards such as ISO 27001 seriously have long since reached levels that NIS 2 barely scratches the surface. The risk is that this Directive runs the risk of becoming yet another ‘regulatory product’ of little use to those who have for years abandoned the state of management of their information systems, neglecting maintenance and modernisation mechanisms that should not be optional, but compulsory and fundamental above all for the proper protection of data.