CSC control number 17 deals with‘Incident Management and Response‘ and is a very topical subject because, starting from the assumption that nobody is invulnerable to an IT incident, one of the main skills to be developed is to be operational again in the shortest possible time.

Preliminary considerations

The CSCs devote 9 safeguards to incident management and response but, before showing them, it is necessary to reflect on the title chosen for this control which, in fact, enshrines two important moments in an incident.

The term management refers to a control activity that begins even before the problem manifests itself. Management therefore requires skills of various kinds that we could summarise as technical, organisational and managerial.

The term response refers to an activity following the occurrence of the incident, necessary for the restoration of the normal situation required by the organisation to operate. Response is only possible if certain conditions are in place, which, of course, must be formed during the management period. There is therefore a dependency relationship between the two moments.

The main objective of incident response is to identify threats within the company, respond before they spread and remedy them before they can cause damage. By not fully understanding the scope of an incident, how it occurred and what can be done to prevent it from happening again, defenders will only ever repeat a pattern as in the game ‘whack the mole’. We cannot expect our protections to be 100 per cent effective. When an incident occurs, if a company does not have a documented plan, even with trained personnel, it is almost impossible to know the correct investigation procedures, reporting, data collection, management responsibilities, legal aspects and communication strategy that will enable the company to understand, manage and recover successfully.

Control #17: Incident Management and Response

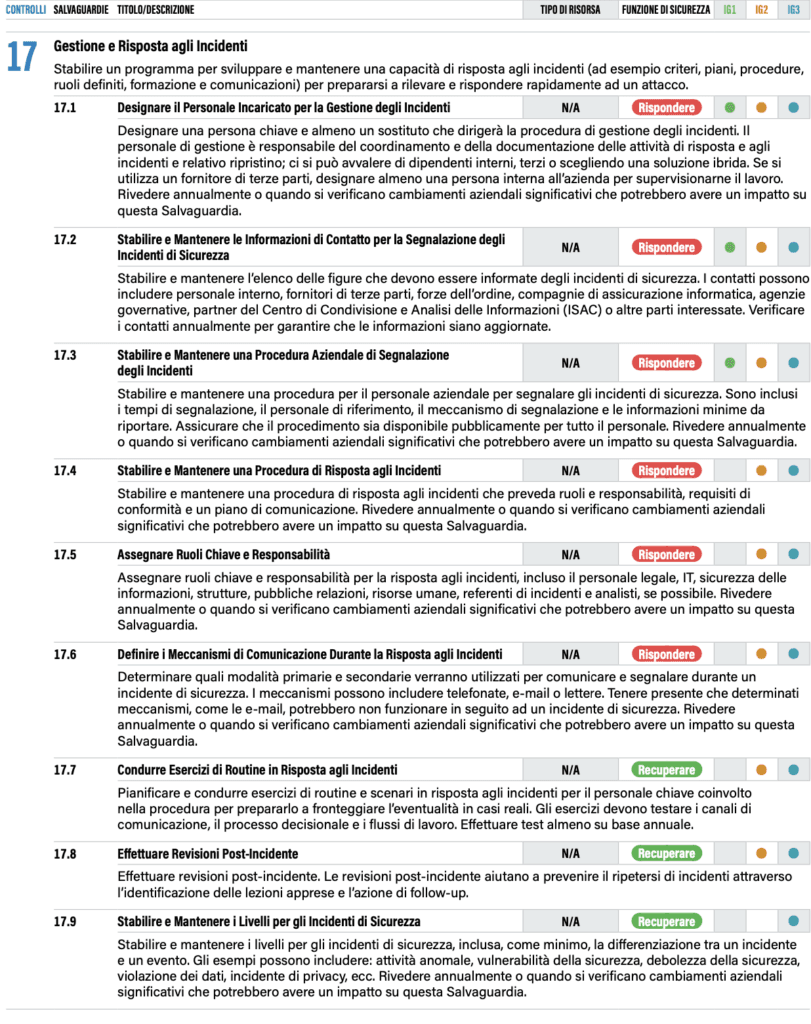

There are nine safeguards in the SCCs and they have two particular functions: RESPONDING and RECOVERY, and as can be seen, many of these measures are based on an adequate capacity to organise resources.

One of the most important aspects of attention is precisely what is stipulated in safeguard 17.1‘Designating Personnel for Incident Management‘. It is customary to think that technical personnel, or perhaps the System Administrator himself, is the most appropriate figure to manage extraordinary events of this type. In reality, this is by no means the case; it is possible that for reasons of experience, specific knowledge or even just temperament, there may be personnel better suited and prepared to manage the computer incident. Among other things, this measure ties in with the next one listed under point 17.5“Assigning Key Roles and Responsibilities“, which precisely aims to distribute roles and responsibilities at various levels (legal, technical, communication, managerial, etc.).

Relationship with CISA

Perhaps not everyone knows that in the fight against ransomware, the US Cybersecurity Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has defined a set of rules to be kept in mind during an incident. These measures include the following:

- Act promptly and simultaneously: assign tasks to several people. For example, when one resource takes care of shutting down the system, the other one disconnects the network equipment. Appointing proxies for action is essential.

- Identifying the suppliers to co-operate with: following an infection, the technicians and operators who will intervene will be different and each with their own skills. Network technicians are different from system technicians, who are different from those who will intervene on NAS and disaster recovery systems.

- Prepare information templates: communicating what happened takes time and therefore it is suggested to prepare email templates and documents to which only some essential information should be added.

These aspects are essential and tie in with the safeguards in control 17 of the SCCs.

Conclusions

Incident management is an essential part of an organisation’s management process. It is no longer understood as an extraordinary event of rare occurrence, but rather as a potentially frequent phenomenon with its own rules and methods of management. Neglecting these aspects produces unpleasant if not problematic consequences: there may be delays in the return to operations, reputational damage but also legal consequences. It is therefore important to prepare appropriate countermeasures to such events and to avert the consequences with good and conscious preparation.