The journey through Critical Security Control, which began with the presentation, continues with one of the most interesting topics: defence against network threats.

Control #09: E-mail and Web Browser Protection

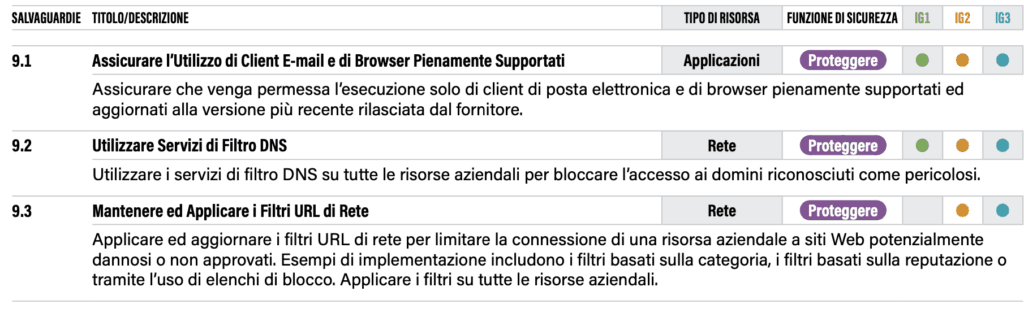

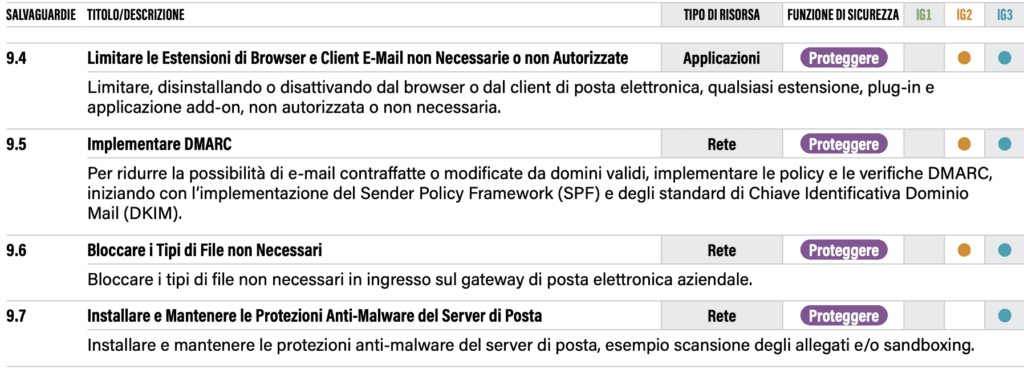

CSCs address the issue of network threats by dealing with email and web surfing. There are seven security measures for category 9 controls, but before examining them, it is necessary to understand the reasoning behind them.

Given that e-mail and the Web are the primary means by which users interact with untrusted people and external environments, they become prime targets for both malicious code and social engineering. In addition, companies’ preference for Web-based e-mail or mobile e-mail access steers users away from more traditional full-featured e-mail clients, which provide built-in security controls such as connection encryption, advanced authentication and phishing warning buttons.

One cannot help but notice the reference to social engineering and the problems arising from multi-stage attacks that can start with a text message(smishing), for instance, amplify with a fake phone call(vishing) and close with a scam carried out on an artefactual web portal. The measures provided for the protection of e-mails and web browsing are listed below.

Here it is necessary to make a not inconsiderable technical remark: unlike the Minimum Security Measures in AgID Circular 2/2017, there is no reference to the automatic opening of emails in the AgID Circular, in fact there was a special rule.

| ABSC_ID | Level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8.7.3 | Minimum | Deactivate the automatic opening of e-mails. |

Those who have tried to implement this rule within organisations and public administrations of medium complexity will have realised how difficult it is to adopt. Staff almost always have the automatic preview box active and do not want to give it up in any way, especially when the list of mails is dense and it is necessary to scroll between mails with the same subject. The AgID measure makes very logical sense: it is known that the automatic opening of an e-mail message could trigger the activation of malicious code. Yet the CSCs seem to ignore this possibility; in reality, what the CSCs do is to focus on the collaboration of several levels of security (including those expressed below in the chapter ‘Defence against Malware’) and on ensuring the correct use of the e-mail client.

On this last point, the more technical will be disappointed: certainly the e-mail client in itself represents a potential vulnerability rather than a security front. However, one must always bear in mind that e-mail clients are often subject to integration with applications such as management or third-party components that could hardly be implemented via the web. Moreover, the e-mail client is still the most preferred medium for employees of companies and P.A., who are often not comfortable with the resources made available by web mails.

Control #10: Malware Defence

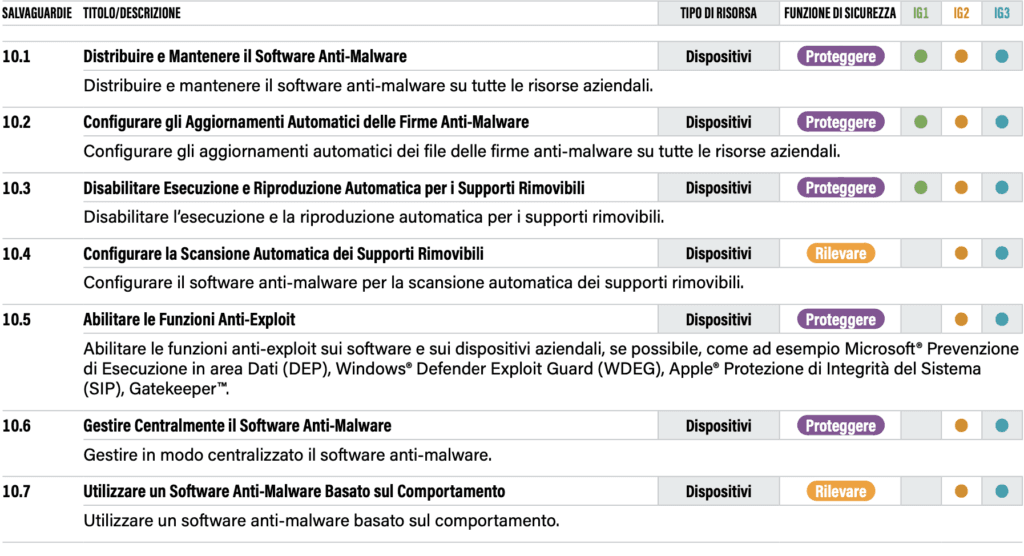

Malware defence’ is the tenth family of critical security controls and is of great interest, especially at a time when it is becoming very difficult to find valid protection from antivirus and anti-malware. The first interesting thing about CSC 8 is that there is perfect awareness of this state of vulnerability.

Modern malware is designed to avoid, deceive or disable defences. Anti-malware defences must be able to act in this dynamic environment by means of automation, constant and rapid updating and integration with other processes such as vulnerability management and incident response. They must be implemented at all possible entry points and corporate resources to detect, prevent the spread or control the execution of software or

malicious code.

The interesting aspect of the above definition is, in particular, the interconnection with other processes dedicated to vulnerability management and incident response. The position of CSCs is therefore very conscious and essentially involves seven controls to counter the malware threat.

Among the safeguards in ABSC 8, one cannot help but notice 10.7, namely ‘Use behaviour-based anti-malware software’. This is a fundamental provision that is also found in the current Minimum Security Measures (the ABSC_ID 8.10.1).

| ABSC_ID | Level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8.10.1 | Standard | Use anti-malware tools that exploit, in addition to signatures, detection techniques based on behavioural anomalies. |

The move from signature-based systems to protection systems based on the recognition of threatening behaviour is crucial, as is the centralised management of anti-malware software.

To some, the measures provided for by the CSCs may appear trivial, but two aspects should be considered: the first is that many small and medium-sized companies still lack centralised anti-malware, or those based on behavioural analysis of the threat. It is not a given to have structures properly ‘equipped’ in this respect.

The second aspect concerns the approach to defence. The latest malware cannot be dealt with by software alone, but technical infrastructure, organisational procedures and checks of various kinds must be added. It is necessary to create a structure based on heterogeneity and therefore particularly effective in dealing with a constantly evolving threat.

Conclusions

Compared to the AgID Minimum Security Measures, the CSCs are much less stringent with regard to e-mail, web browsing and protection against malware. However, it must be considered that the approach is different, as is the final target. However, it is important to note the tendency to create a cooperating ecosystem and not simply thematic cybersecurity verticals.