We continue to use the term artificial intelligence to describe a discipline that currently has very little in common with the meaning of the word intelligence. Let us delve deeper into this concept.

The term artificial intelligence refers to two very different concepts: the first is the entire state-of-the-art technological discipline based on the replication of complex human mental processes. The second is the first evolutionary step1 of that discipline. The problem is that, at least at this point in time, the term intelligence is not really representative of the current condition in which these technologies operate.

Intelligence: what it is

The term intelligence comes from the Latin intelligere meaning ‘to understand’. The Treccani provides the following definition:

Complex of psychic and mental faculties that enable human beings to think, understand or explain facts or actions, elaborate abstract models of reality, understand and be understood by others, judge, and at the same time make them capable of adapting to new situations and of modifying the situation itself when it presents obstacles to adaptation.

Source: Treccani

Already in this definition, one can realise that intelligence is not limited to the execution of processes but rather to their understanding, i.e. their examination in a context of abstraction as well. Of course, to do this, the human being adopts (and adapts) his knowledge, the elementary part of which is notion, but he also has a further, much less rational factor at his disposal, namely intuition. Both these elements are concentrated in a much more compressed level that we tend to describe with the word experience. In it, the logical links are juxtaposed without immediate visibility although they can then be revealed with more careful and detailed analysis. The Treccani itself, moreover, sets out an interesting definition of intelligence in the cybernetic sphere:

In cybernetics, artificial i. (translation of artificial intelligence), partial reproduction of man’s own intellectual activity (with particular regard to the processes of learning, recognition, choice)

Source: Treccani

It is therefore a reproduction, i.e. a copy and not an authentic process, at least not at this early stage of evolution.

Substantive and marketing reasons

The name is therefore misleading, but it certainly has a great impact at the level of marketing and communication: the term artificial intelligence arouses a series of emotional reactions within the public that one can hardly do without if one wants to sell such a product. Complex as they are, current artificial intelligence algorithms revolve around predetermined notions and processes, there is no real ‘understanding’ of words, there is no ability to process abstract concepts. To the end user, it seems as if we are witnessing an extraordinary achievement: that of a machine capable of dialoguing with a human being and that of performing even quite complex tasks. In reality, when breaking down these tasks, there is an intricate complex of notions and instructions ‘and nothing more’. This does not make the technology in question any less important: in healthcare, for example, it is revealing its usefulness day by day. However, it is good to focus on the meaning of the word intelligence, because it means something more.

Modern language and artificial intelligence

In the modern era, a bad practice has become established, that of establishing exact concepts behind words: in essence, it means that people try to attribute a well-defined meaning to words such as intelligence, but in reality, this is not always possible. It is an extreme exemplification process that is leading individuals to consider that there is a meaning behind a word, mostly identifiable and parameterisable. In an interview2 by Carlo Sini, the philosopher makes this clear:

We have to stop thinking that there are things behind the words, that even the word intelligence says what intelligence is because obviously intelligence is a complex of functions, of inheritance, of symbiosis…

That is, the word intelligence describes aspects that are anything but single, defined, specific, but rather defines more complex and in some ways more abstract contours. On the other hand, Sini’s vision is much less marketable: how to explain to a consumer what artificial intelligence is if it is, in itself, much less identifiable in a thing, in a product, in a finished element? The reduction made by marketing, which sometimes demands extreme exemplification, risks creating a misleading end result.

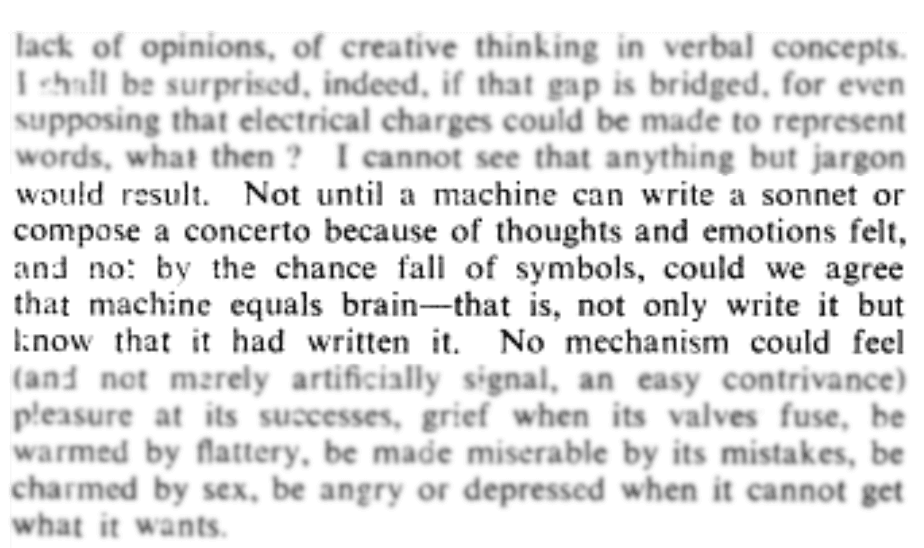

But if the current one is not true artificial intelligence, what can be called such? In 1949, Professor Jefferson3, addressing the issue of machine self-awareness, wrote:

Until a machine can write a sonnet or compose a concerto on the basis of thoughts and emotions felt, and not by the random juxtaposition of symbols, we cannot agree that a machine equals the brain – that is, that it not only writes but knows it has written.

Geoffrey Jefferson, The Mind of Mechanical Man, British Medical Journal 1949

Jefferson introduces a number of undoubtedly complex aspects: the concept of felt emotions and the requirement that intelligent execution takes place not by random juxtaposition of symbols. Yet the most important aspect of Jefferson’s definition is that artificial intelligence, in order to be compared to human intelligence, should not merely write but know that it has written. In this concept lies all the complexity we are talking about.

We could also mention Godel’s theorem to address the topic of artificial intelligence and machine self-awareness. The theorem states that in a powerful computational system, statements can be generated that, at the same time, cannot be proved or disproved within the same system, unless the system itself is contradictory.

What Godel is talking about is, essentially, the development of critical thinking. In order to prove the thesis, in fact, the system should necessarily contradict it with an effective and realistic antithesis.

Language, Logic and Computation

John Von Neumann’s studies, although conducted around 1950-1960, proved to be very accurate and today fuel much of modern theories and calculations. Essentially, we know, thanks to Von Neuman, that the brain is not a serial machine and therefore, although beaten in speed by the modern computer, is capable of excelling in computational complexity. This is possible thanks to the ability to parallelise synaptic computing resources in a way that the machine, at present, cannot.

However, despite the accuracy of Von Neuman’s estimates, there is another aspect to consider: calculation is a human creation and does not follow a criterion of direct efficiency, but rather ‘suffers’ from certain aspects typical of language.

It should be understood that language is largely an accidental historical fact […] there is nothing absolute and necessary in them. […]Similarly, it is reasonable to assume that even logic and mathematics are equally historical and accidental forms of expression.

Source: ‘Computers and the Brain‘, J. Von Neuman, il Saggiatore (2021), p. 138

The process of language mutation is inexorable and clearly follows social development: what Prof. Vera Gheno writes on this subject is very interesting.

Languages are nothing more than a tool to communicate: we and what is around us are constantly changing and therefore language also serves us in a changing reality. We have to embrace change, because if a language stops changing it will die, which is what has happened to many languages.

Source: ‘”Youth and social are changing Italian. But it is not a bad thing’. Linguist explains why’, article by Duccio Tronci, published in Firenze Today on 16/09/2021, link to the article.

Logic, like language, could undergo radical mutations over time that could change the way in which current computational problems are approached.

Complexity and rationality of language

Our language is descended from Ancient Greek and Sanskrit. Ancient Greek is a sophisticated, refined language, full of nuances to be applied to various situations. Apparently, there is no efficiency in it. We are used to thinking that efficiency is achieved by reducing effort and maximising the result, that efficiency is in simplification, not complexity.

Of course, our language may not be efficient, but it is certainly effective. Human beings think on the basis of the words they know: the more words they know, the more they are able to formulate complex thoughts. As long as a young person does not know mathematical operations, he is not able to perform either addition or subtraction, yet he has the computing power to perform them. History and evolution are an essential element in the modification of language, of logic: among other things, it is worth noting that the term‘logic‘ is descended from the Greek‘logos(λόγοσ)’, which means word but also calculation.

Emulation

In some texts and articles on artificial intelligence, the term emulation has been used. An example is what was written by Ilya Auslender, a research fellow at the Physics Department of the University of Trento. One has to think about this term because the end result is interesting. The concept of emulation exists in computer science with a precise meaning:

Artificial intelligence emulates the functioning of the brain. Therefore, it can be used in the reverse process to understand certain functions of the brain, up to a certain level of accuracy, on the basis of experimental data from the analysis of an artificial neural network.

Prof. Ilya Auslender ‘Artificial intelligence to understand the human brain’

In computer science, emulation is the ability to reproduce and transfer the calculation capacity of a primary system into a secondary system, which is called an emulator. For this to succeed, however, an essential requirement is necessary: that the performance of the secondary system is equal to or better than that of the primary system. Otherwise, the secondary system could not effectively ‘host’ the emulation of the primary system, which would be too powerful. Outside of computer science, the term emulation still has a place:

Trying to equal or surpass others in works worthy of appreciation.

Source: Treccani

The artificial intelligence we currently have at our disposal does not equal or even exceed human intelligence, but emulates a part of it limited to specific tasks, at the basis of which there is a considerable amount of calculation and refined processing. An illusion? Not exactly.

Rather than an illusion, it could be described as a partial emulation of human cognitive processes in which the aim is not the replication of intelligence (an abstract and very broad concept), but the artificial replication of specific groups of cognitive processes. Of course, this should not detract from the enormous amount of work behind such a procedure, but neither should it suggest that the human mind can be ‘caged’ within a few million lines of code.

Conclusions

Artificial intelligence, at the moment, cannot be defined as truly intelligent despite the enormous efforts it has made to guarantee computational complexity and a refined and amazing user experience; this needs to be clarified without wishing to diminish its importance. The comparison between a human brain and an artificial brain is among the most interesting topics in neuroscience (and not only), but it must be framed in a perspective of cooperation and not substitution. If modern society is designed by man and adequately supported by technology (an equation that hopefully will never be reversed), there will always be a balance between the human and artificial worlds.