There have been so many attacks on the Italian public administration and there will continue to be more: the surprise effect should no longer exist and should give way to righteous indignation over the lack of recovery in due time and manner.

Hacker attacks are a normal condition

Hacker attacks are a normal condition; they are part of ‘life on the Internet’, affected by geopolitics, economic development and many other factors. Offences on the Internet are comparable to drivers committing a traffic offence: it is a dangerous but frequent condition, so frequent that it has become normal. This does not mean dismissing the facts or not prosecuting them legally, it means making sure that they are dealt with correctly: without fuss about the attack itself but firmly where data protection rules have not been observed.

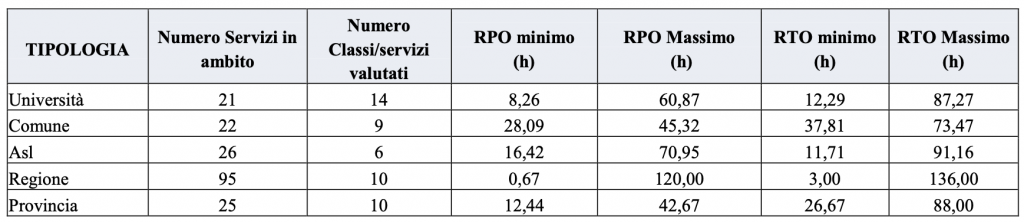

On more than one occasion we have spoken, for example, of the valuable work done by AgID in identifying service levels (SLAs) that can be adopted by the various types of public administration. On those occasions, however, it was noted that these SLAs are rarely observed despite the fact that ten years have passed since their publication (it was 2013).

Over time, a convenient (and also very dangerous) behaviour has developed in connection with cyber attacks: blaming the hacker without taking responsibility for the failure to comply with protection standards and criteria. Yet these shortcomings, which are certainly exploited by hackers, were there even before the attack.

Attributing the right responsibilities

Analysing the findings of data breaches, one cannot fail to notice, in most situations, confusion in the management of data, services and systems, or even a certain laxity in choosing the ‘most convenient’ and least secure settings. The most classic example is the huge amount of access credentials to institutional portals that municipalities and regions hold in ordinary text files in TXT format. Files that are not password-protected, and which are completely unsuitable for storing that type of information. Why can’t the P.A. equip itself with appropriate keyrings, which are robustly encrypted and represent the correct way to manage credentials?

Undoubtedly, the hacker is responsible for an attack, and so is the exfiltration of data, but the security of the data is the responsibility of the public administration, and so is the manner and timing of recovery. This is what should astonish, outrage and create debate: not the attack itself, which, unfortunately, is a normal occurrence. When one looks at the EDPB case studies, one can see how, even in the presence of data exfiltration, if the data have been appropriately encrypted, communication to the Garante is not necessary because the hacker will not be able to read them.

It follows that the data breach described above is unlikely to pose a risk to the rights and freedoms of data subjects, so no notification to the supervisory authority or data subjects is required. However, even such a breach must be documented, pursuant to Article 33(5)

Source:‘Guideline 01/2021 on examples concerning the notification of a personal data breach‘, EDPB (Case 10, Pg. 22)

In essence, the EDPB has realised that a hacker attack is a frequent condition that can only be dealt with effectively through preventive actions. So, simplifying a lot, whose fault is it that data is not secured? The hacker who carries out the cyber attack, or the user who, despite having to and being able to apply those measures, decides not to implement them? By the way, we are not talking about ‘recommendations’, advice or suggestions, but about real measures established through legal obligations.

The question of economic resources

The most common response when investigating the cause of a data breach is that there are no economic resources available. This is the explanation for the lack of planning of control measures, the failure to design adequate infrastructure, and the failure to implement policies for monitoring. However, all this is very strange because the P.A. is obliged to carry out the three-year IT plan and thus to provide appropriate economic resources for the development of ICT services and security.

The Three-Year Plan for Information Technology in the Public Administration (Three-Year Plan or Plan) is an essential tool for promoting the digital transformation of the country and, in particular, that of the Italian Public Administration, through the declination of the digitalisation strategy into operational indications, such as objectives and expected results, traceable to the PA’s administrative action.

Source: AgID(link)

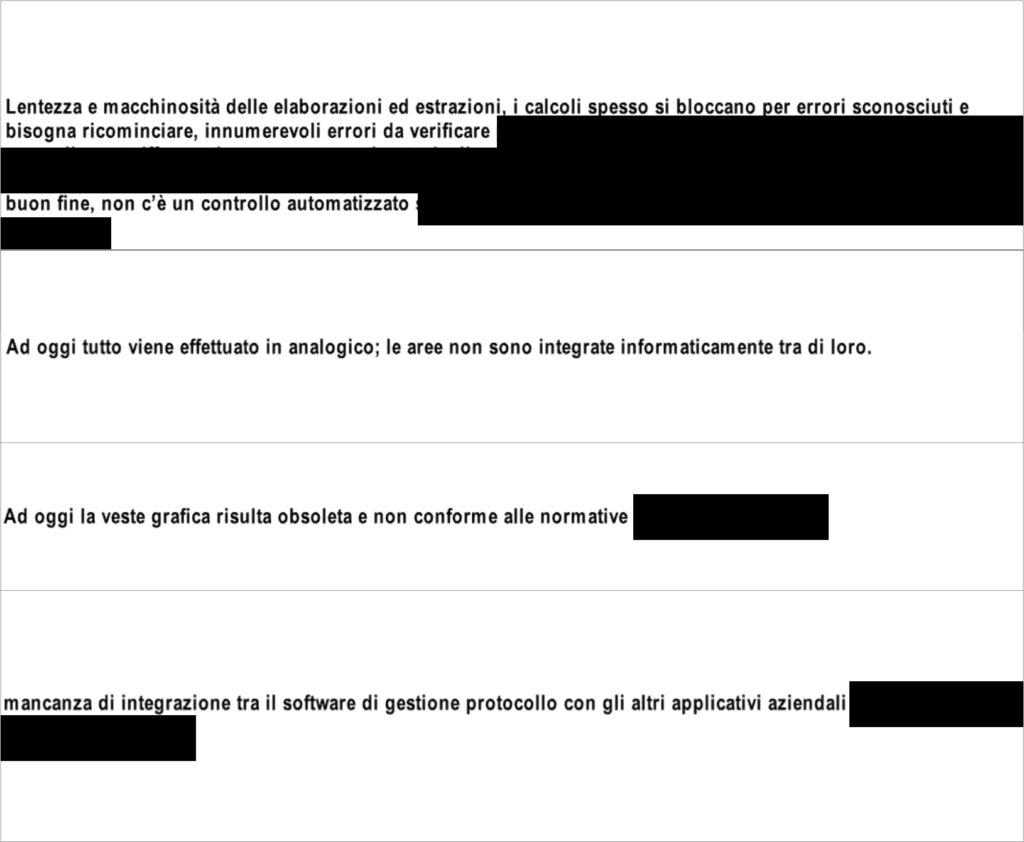

IT security is part of that strategy that AgID talks about, but the truth, as is often the case, is more complex in its simplicity: economic resources are often allocated without a real planning criterion, but rather entrusted to different suppliers who try to grab the largest share with projects that produce a ‘disjointed’ growth in the IT infrastructure. There are also public administrations that directly entrust suppliers with the writing of the Three-Year Plan, thus favouring a bias in projects and development strategies. This aspect opens up a second front for reflection: the lack of mastery and culture of security and architectural issues within many IT departments, which prevents, among other things, the proper exercise of configuration control(for more details click here).

The cloud and the ‘proxy’ model

In Italy, IT security in the public sector began to undergo a slow transformation when, especially with fibre, it was decided to entrust data, services and applications to the cloud. This was supposed to simplify the implementation of security measures and create more secure operating environments. However, it generated a distortion in many cases: the migration of databases and applications was carried out in such an uncontrolled manner that it resulted in lock-in phenomena towards certain providers.

The cloud, by the way, has been hailed as the panacea for all ills, which, in reality, it absolutely is not: wrong architectures, wrong approaches to data management, carelessness in archiving documents considered of little importance when in fact they are very important persist. A few weeks ago, an Italian municipality was hit: among the data exfiltrated were also those of the social affairs office. A patient’s psychiatric diary was scanned and used to justify the request for funds.

During a conference I was asked what the problem was in having this kind of information in a file and, above all, in attaching it to the request for psychological support. In order one could quickly answer that:

- This information should be protected by encryption or otherwise not easily accessible.

- This information is not necessary to make the request for psychological support, a doctor’s certificate is sufficient (as was the case on other occasions in the same municipality). All the more reason, since this is a renewal, there is no need to attach documents of this magnitude.

- Such requests should present anonymised/pseudonymised information about the patients (as was the case on other occasions in the same municipality).

There was some silence and the hearing officer replied by saying that indeed these were valid considerations, that he did not know how to apply protection to the individual file and, as for anonymisation/pseudonymisation, that perhaps the problem lay at regional level. Indeed, the Region demanded a ‘certain’ certificate in order to disburse psychological support funds, but this does not mean that it is necessary to email a patient’s clinical diary with all his therapeutic data in plain text.

A generational but also a political problem

Over the years, students on master’s and degree courses have developed a growing sensitivity to the issue of personal data protection. Undoubtedly, more controlled and protected management will be achieved, but time is the worst enemy in conditions like these; the case of the psychologist’s notes, reported earlier, is a shining example of the problem.

There is a considerable disconnect between the global political vision and the local political vision; a global vision so far removed from reality that one is sometimes unaware of the measures to be taken. During a survey of critical issues within a local P.A., so many anomalies of a macroscopic nature were found that, halfway through the survey, the working group called a meeting to talk to the management.

The Director General, reading the findings analysed so far, concluded that the situation was not as serious as the employees portrayed it to be and that there was certainly a lot of misinformation. On the basis of what the management arrived at these conclusions is not known to this day, whereas the computer incidents that marked the activities of that P.A. in the following months (to the detriment of citizens) are known.

Conclusions

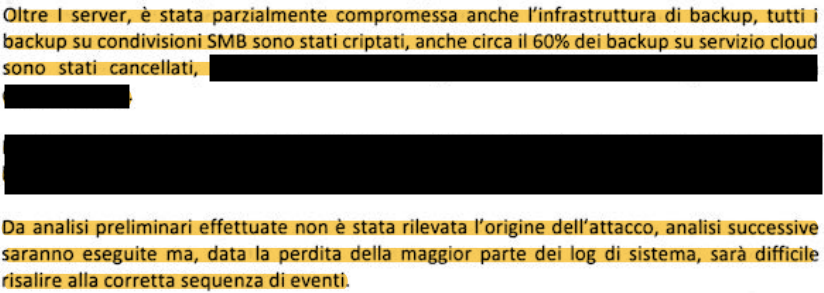

The spectacularisation of hacker attacks does not exclude the responsibility of local administrators for neglecting rules and dictates. It is necessary to demand compliance with service levels and to be indignant when, for example, healthcare facilities remain blocked for 30 or 50 days. It must become unacceptable to read that backups have been lost, destroyed, that they have been encrypted.

It is important that there is proper accountability when sensitive information, such as clinical diaries, medical examinations, court papers, personal data of a special nature, is poorly kept and inadequately protected.

The real ‘scandal’ is not the attack itself, but the complete carelessness with which data is often maintained within information systems; this needs to be convinced of or people will continue to blame someone else for responsibilities they do not really have.