We continue to talk about Artificial Intelligence in every field, but it is also important to understand the social context in which this technology is set.

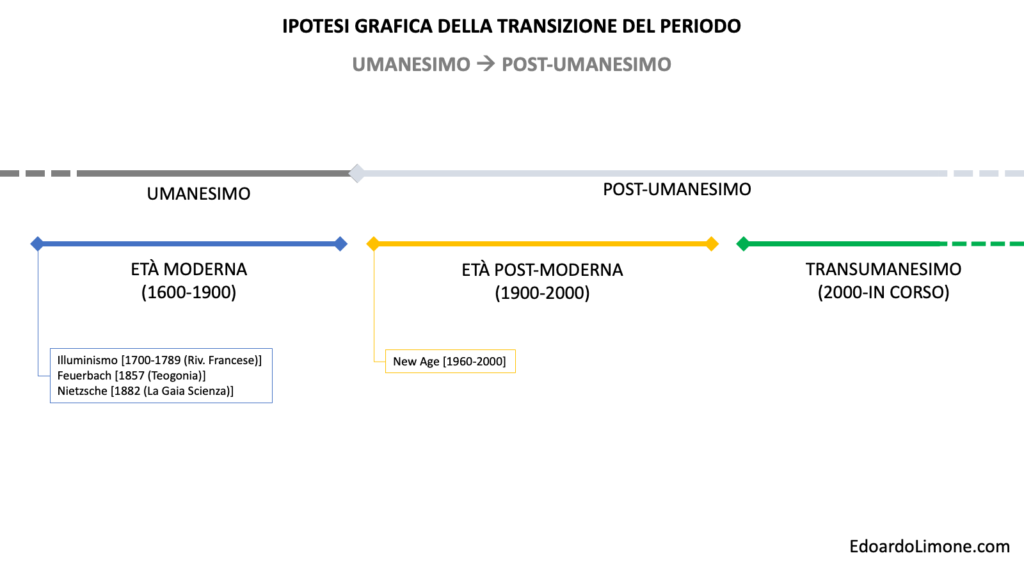

In an attempt to reconstruct the transition from Humanism to Post-Humanism, in this article we have focused on two specific historical periods: the Modern Age and the Post-Modern Age. Transhumanism will be dealt with later as a current period of scientific discovery and research. If in Humanism the initial condition was that of a man subject to the inviolable rules of nature, around which those of society, religion and politics revolved, gradually the situation changed. The modern age, as we shall see, marks a strong break with traditional patterns and opens up to a more anthropocentric and less subordinate vision of the human being. This situation will remain substantially unchanged until the post-modern era, when scientific discoveries will allow the introduction of a new component into the anthropocentric scenario: that of the artificial intelligence currently being studied. The present is a period of great changes, of great questions: if law is one of the highest expressions of the anthropocentric vision, how should its extension to an artificial intelligence context be understood? The doubts that, correctly, jurists are asking about the responsibilities of the algorithm and the provider are the questioning of that anthropocentrism that has characterised the modern era.

The current era straddles post-modernity and transhumanism, but it is necessary to start the analysis from the modern period for clarity.

Modernity

The age of modernity has been pervaded by technology: this has been discussed extensively in this article with reference to Heidegger’s vision and the philosopher’s extraordinary foresight. The modern age has a very ancient beginning: we could trace it back to Galileo and Bacon, to a period when science explained reality in pieces and then offered an incontrovertible vision of it.

Modern science completely isolates the parts, which it examines, i.e. it does not address the totality of being. And yet, at its inception, it presents itself as incontrovertible knowledge.

Source: ‘La Filosofia Moderna’, E. Severino, Bur, 2023, Pg.53

It is a process aimed at offering a ‘tangible concreteness of reality’, something that can explain and modify the individual’s perception of life. Severino himself wrote, with regard to the idola in Bacon’s philosophy, that “true science is true power over nature, and therefore the capacity to mitigate man’spain1“. The dominion that man has slowly seen fit to assert over nature has been perpetrated thanks to technology, about which much could be said, including that it only has a value relative to man himself. Nature proceeds independently of it.

It is crucial to consider two factors in the evolution of modern thought: action and time. Neither has any real importance in the context of nature: the individual action (εργον) is the basis of technical activity. In the modern view, action is parameterisable and forces nature to be subject to parameters to which it must respond. Bear in mind that even the most accurate of scientific experiments rest on theoretical assumptions that are not present in nature (e.g. the point, the line, the plane). In fact, today, many of the scientific disciplines that used to be established as unquestionable are aware that they work on assumptions2.

Time is an extraordinary human invention: used to give importance to the lives of men on Earth. Presumptuously we could call it the toy of men’s memory, less presumptuously we could call it a metre that exists only for human beings and not even for everyone equally. If Heidegger stopped to analyse the various types of time use3 (linear, circular, etc.), on the other hand, it is impossible not to realise that nature does not need time for itself. Nature lived, lives and will live outside time.

Those who, on the other hand, are in great need of time are human beings and, in this case, technology as the ultimate expression of capitalism and the rationalisation of technological evolution. The expression time is everything coincides with a reality that is subjected in almost all its aspects to a temporal logic. The cost of labour is in man-days, calculation processes are measured on a time basis, speed itself is on a time basis (e.g. 130 km/h).

Consider that modernity has included events and personalities such as:

- Enlightenment: 1700 – 1789 (French Revolution), but one must consider that the end of the movement in Europe and the United States was slower.

- Feuerback: 1857 with his famous Theogony.

- Nietsche: 1882 ‘Gott ist tot! Gott bleibt tot! Und wir haben ihn getötet (God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him!)”,Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gaiety of Science [1882], III, 125, translated by F. Masini, in Opere, volume 5, tome 2, Adelphi, Milan 1965, p. 130

Postmodernity

The transition from modernity to postmodernity took place from the 20th century onwards and was a slow and inexorable process; the term postmodern can be traced back to the capitalist crisis and 1960. The transformation can be analysed from many aspects: social, religious, technological, and each of these is connected to the others. From the technological point of view, for example, a great starting point was cybernetics, whose father was the mathematician Norbert Wiener. His studies are the basis of the postmodern era, which is characterised by the integration of organisms and technologies or, to be clearer, between organic beings and electronic technologies (remember that Wiener hypothesised the construction of an organic artificial memory in 1964). At the basis of the postmodern era, there is therefore a macro-economic component, as well as a social one. At the end of the 20th century, the New Age asserts itself as the translation of all these cultural drives within the social context; and with it, the relationship between man and spirituality is also irrevocably changed. New religions, new philosophies, new ways of living are born that all have one thing in common: the ability to experience the mystical dimension directly. Drugs, alternative therapies, rituals, directly affect the state of consciousness of the individual in search of a more tangible plane of confrontation than the traditional one.

The religious component

In order to understand the evolution of postmodernity, it is therefore essential to also take a look at the transformation that has involved religion and society over the years. The post-modern era has forced religion to reflect on the social change taking place, based on a delocalisation of the oldest religions, to the prerogative of new beliefs perceived as being ‘closer’, more ‘real’ and more comprehensible. On the threshold of 2000, there was a conference organised by the Theological Faculty of Northern Italy in which the theologian Pierangelo Sequeri spoke among the speakers:

The narcissism of a gnostic religion and the despotism of a sacrificial religion transcend into each other, feeding on the same arguments and aspirations. The religious self-referentiality of the I-atom and that of the I-mass are now only superficially distinct in postmodernism.

Source: ‘La Religione Postmoderna’, AA.VV., ed Glossa (2003), Pg 81

Post-modernity has established a different and self-referential dimension of the self; this has led to the crisis of a series of religious and spiritual values that no longer found their rightful place within the individual. In the process of re-evaluating the spiritual-religious dimension, there is the perception that the human being frees himself from a God that he suddenly perceives as distant and unsuitable for understanding reality. Sequeri himself, on the occasion of that conference, stated:

The search for a personalised religiosity, in fact, is not to be seen merely in the form of the pure and simple abandonment of traditional religion. On the contrary. Nor is it expressed in the sheer drift of wild de-institutionalisation or individualistic gratification.

Source: “La Religione Postmoderna”, AA.VV., ed Glossa (2003), Pg. 71

Postmodernity is therefore a historical period of revaluation of principles and values that produces entropy: we stop believing in God and start believing to believe as Vattimo would say. Perhaps it is the title of Vattimo’s work that best represents the relationship between religion and post-modernity: ‘Believing to believe. Is it possible to be Christian despite the church?”. If man is indeed detaching himself from religion, as Severino also wrote, it is in order to orient himself no longer towards a zone of mystical sacredness but towards something different.

Relying on God begins to appear as alienation and man’s renunciation of himself, when it is no longer believed that God’s infinite power is something existing.

Source. ‘The Decline of Capitalism’, E. Severino, BUR, Pg. 139

This ‘something’ is based on experience and therefore responds to a phenomenological, empirical, experiential, sometimes even tangible but not entirely explicable plane. Many modern technologies are perceived as ‘surprising’, ‘marvellous’. bordering on the mysterious (also thanks to very effective communication), artificial intelligence is certainly among them.

The technological component

The spread of technology has led to a generalised massification of the interpretation of the contemporary world, following models far removed from the traditional ones and favouring the creation of social fractures that have undermined the identity of the individual. This has led, on the one hand, to a social isolation discussed in many sociological texts, and on the other, to the need to associate in shared groups and contexts as a reaction to this phenomenon.

We must therefore critically ask ourselves what is the best way to disseminate such a relevant and pervasive technology in order to avoid not only economic but also social ‘backlashes’. An interesting expression of this phenomenon is given by Franco Riva, Professor of Social Ethics at the Università Cattolica del S. Cuore in Milan.

Freedom no longer knows what to do with itself. It has become superfluous to itself, useless because it is always being surpassed as it asserts itself, and tediously asserted as it is being surpassed.

Fear of technology

Fearing something, someone, forces us to adopt an attitude of caution. This attitude is functional to study the other, to study intentions, to orient ourselves towards understanding or, in the least of cases, towards intuition. What one fears, one must necessarily understand in order to avert its consequences: technology is not feared even though it is capable of producing numerous social consequences.

The first point to make is that technology should not be feared: it is objectively a source of evolution, social improvement, and the dissemination of culture. It is a fundamental human right to access a valuable resource like the Internet, it says on the European Union website:

In any part of the EU, you must be able to have access to good quality electronic communication services at an acceptable price, including basic Internet access. This is the so-called ‘universal service’ principle. There should be at least one Internet service provider that can offer you this service.

Source: European Union(link)

But experience with a technology should not lead one to overlook the implications for its proper use. The opportunity may conceal complexities and consequences that should not be underestimated. Caution then is a must and should prompt careful analysis before proceeding to deployment and adoption.

In the wake of this, ‘catastrophic visions’ were realised regarding the possible consequences of out-of-control progress, but at the same time, those hopes that always linger in men’s souls re-emerged: defeating disease, conquering awe and pushing death away to the point of attempting to eliminate it

Source: ‘Posthumanism and Philosophy’, Claudio Bonito, Mimesis Publisher (2022), Pg. 28

Conclusions

Consider a specific moment in the cultural history of the 19th century, the one that led to the birth not only of the Enlightenment but also of the ideologists. Both currents had had as their reference the mathematician Condorcet, thanks to whomthey ‘had dreamed of discovering and applying mathematical laws that would rationally and justly regulate the making of decisions in courts, assemblies and elections or serve to govern the economy‘4.

It is impossible not to notice how long society has been preparing for digitisation: through studies of process rationalisation, but also through not indifferent anthropometric analyses (think of what Craik analysed). The road is much longer and older than it appears at the moment.

Yet this must give rise to some reflection: one must question, for example, the ethical use of the most advanced technologies. The decision must be subjected to a careful assessment of respect for the community, which cannot be made by the marketing department of a company, or by the social media manager. It is essential to return to the substance of concepts: getting away from the eternal simplification that plagues our age; there is nothing wrong with simplifying, but when this process is forced, the result will not be appreciable. Over-simplification leads to trivialisation, and trivialisation of social values cannot lead to anything good.

Simplification is a praiseworthy action aimed at reducing complexity while maintaining the overall character of an idea, of a process. This may also involve retaining a certain degree of complexity as a structural element of the idea or process. In essence, one simplifies what one can but retains what is needed for the necessary functioning of the idea/process (remember that bureaucracy is partly retained because it is necessary, it is generally called ‘healthy bureaucracy’).

Trivialisation is the reduction of the idea/process to minimum terms of understanding without concern for safeguarding any nucleus of possible necessary complexity, consequently not caring about any transformations of meaning or interpretations that the change may bring and/or entail. Perhaps it is worth concluding this article with a phrase by the surgeon and Nobel Prize winner (1912) Alexis Carrel:

Thanks to self-knowledge, humanity, for the first time since the beginning of history, has become master of its own destiny; but will it be able to use the unlimited power of science to its own advantage?

‘Man, this stranger’, Alexis Carrel, 1937

- “La Filosofia Moderna”, E. Severino, Bur, 2023, Pg.59 ↩︎

- One thinks of Descartes’ philosophy on the appearance of the world but, more recently, of Nietsche’s statement‘no, facts really do not exist, only interpretations exist‘. ↩︎

- “The Concept of Time”, M. Heidegger, Adelphi, 2023 ↩︎

- “The World as a Mathematical Game”, G. Israel, Bollati Boringhieri (2018), Pg.13 ↩︎